When people get together for Christmas or other festive events they often play games. There’s Charades, especially for when a few drinks have been taken, or board games (often ending in family arguments).

When people get together for Christmas or other festive events they often play games. There’s Charades, especially for when a few drinks have been taken, or board games (often ending in family arguments).

Then there’s the one where you have a post-it note with a name stuck to your forehead and you have to guess who you “are” (and which led a dear friend of ours to declare he would never come to our house again if he was going to be made to play games, which was duly noted).

For the Surrealists, games were a very serious business, providing the conditions for spontaneous creativity and the element of revealing self-exposure, which might throw up new truths. The fun, pleasure, playfulness and random co-incidence of games were at the heart of what the Surrealists were trying to do: overturn normal society and liberate the imagination.

Everyone knows that play is part of art-making, and the fun that the artist or writer has in creating art can seem a little suspicious in our economically-driven, status-obsessed world. It was precisely the subversive aspect of games that the Surrealists liked so much. To play is to abandon the adult world, pleasure is the aim and there is no material reward guaranteed. Playing means ignoring what is serious, or urgent, or economically productive, and it is a great leveller. It conquers time, too, because a game ends only when the players are ready to stop, meaning that normal life or work is suspended.

Artists play with their materials: paint, colour, line, brush, knife, wood or stone. Writers play with stories, words, and the sound of words. To be creative is to play; it is to work at playing in the sense of doing on purpose, and in a sustained way, what the child (if happy, healthy, etc) does spontaneously when alone or with others.

In the creative writing course I ran for the now defunct Lifelong Learning at Bangor University we played a lot of Surrealist games and the sense of freedom and permissiveness created a mood and space in which laughter and creativity were blended together. The group were brought together by the games played in teams and the risks that were required in terms of individual contributions. Unfortunately when I tried to induce the full-time students to play games in class they seemed to be, at 19 or 20, unwilling to throw off the dignity of adulthood (unlike my “mature” students who were game for anything!).

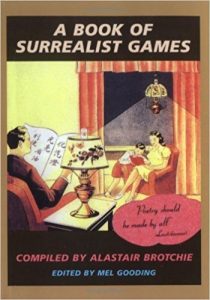

Most of the games played by Surrealists, from the days of the Paris group in t he 1920s to the very recent Chicago group were never recorded, but much survives in various publications and manuscripts. One of my most treasured possessions is “Surrealist Games” by Alistair Brotchie: a wonderful box of delights which contains a book, board game, Surrealist dictionary and what seems to be an iron-on transfer. In it, after an excellent introduction by Mel Gooding, are instructions and examples of Surrealist games grouped together under headings such as “Language Games,” “Visual Techniques” and “Re-Inventing the World”.

he 1920s to the very recent Chicago group were never recorded, but much survives in various publications and manuscripts. One of my most treasured possessions is “Surrealist Games” by Alistair Brotchie: a wonderful box of delights which contains a book, board game, Surrealist dictionary and what seems to be an iron-on transfer. In it, after an excellent introduction by Mel Gooding, are instructions and examples of Surrealist games grouped together under headings such as “Language Games,” “Visual Techniques” and “Re-Inventing the World”.

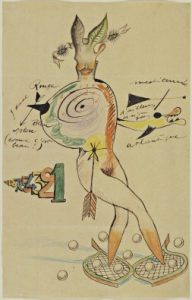

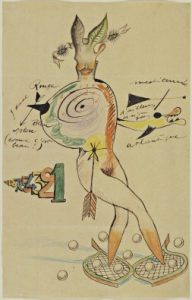

The best-known collective game is The Exquisite Corpse which grew out of the game Consequences. On a piece of paper, write “a” or “the” and an adjective (such as “exquisite”) then turn down the top of the paper to hide what you have written and pass it to the next person. He or she adds a noun (e.g. “corpse”), hides it in the same way and passes it on again. The next person contributes a verb, then it’s “a/the” plus an adjective and finally another noun. The paper is then unfolded and read aloud and curious “poems” are discovered to have been collectively written, such as the first which was “The exquisite/ corpse/ shall drink/ the new /wine” which gave the game its title. Visual “Exquisite Corpses” can also be made. Here is one from 1927 by Yves Tanguy, Joan Miro, Max Morise and Man Ray.

There are other “chain games” in the Brotchie box which have the same method of writing then concealing what you have written then passing it on, and the idea is that a sort of collective unconscious takes over. We certainly found that a sort of synchronicity was occurring in the classroom with either weirdly “logical” collective creations or unexpectedly beautiful combinations.

There are other “chain games” in the Brotchie box which have the same method of writing then concealing what you have written then passing it on, and the idea is that a sort of collective unconscious takes over. We certainly found that a sort of synchronicity was occurring in the classroom with either weirdly “logical” collective creations or unexpectedly beautiful combinations.

Conditionals is a chain game using the folded-over technique that’s easy to play (and I have a scene in my novel where it’s played by the characters). There are only two stages. The first person writes a sentence beginning with a hypothetical idea starting with “if” or “when” and turns down the page. The next person writes a sentence beginning with “then” or casts it in the future. Here are a couple of the ones in Brotchie so you can see how it works:

“If there were no guillotine

Wasps would take off their corsets”

“If octopi wore bracelets

Ships would be towed by flies”

The game of “One Into the Other” might be one you could play at Christmas parties. You need at least three players, more is better. Here are Brotchie’s instructions:

“One player withdraws from the room, and chooses for himself an object (or a person, or idea, etc.). While he is absent the rest of the players also choose an object. When the first player returns he is told what object they have chosen. He must now describe his own object in terms of the properties of the object chosen by the others, making the comparison more and more obvious as he proceeds, until they are able to guess its identity. The first player should begin with a sentence such as ‘I am an (object)…’”

Here is Benjamin Péret who chose the Milky Way as his object and was asked by the others to describe it in terms of a breast:

“I am a very beautiful female breast, particularly long and serpentine. The woman bearing it agrees to display it only on certain nights. From its innumerable nipples spurts a luminous milk. Few people, poets excepted, are able to appreciate its curve.”

Not all Surrealist games require a group of players but the playful aspect of group games permeates Surrealist art and writing that has been created by individual effort. Automatic writing is the pre-eminent Surrealist game-for-one and you can find instructions at https://www.freewriterscompanion.com/howtofreewrite/. Brotchie includes another of the many possible ways of doing automatic (or free) writing in the game Simulation, much beloved by Salvador Dali, in which you write as if in an unusual mental state. Dali liked to simulate madness but what about trying to write as if in the grip of illness, drunkenness or zero gravity? As an animal, or object? Or even as another person. After all, that’s what fiction is all about…

Making a story or poem can be turned into a game by following the Dada cut-up procedure. Take a magazine, newspaper or book (if you can bear to destroy it!) and cut out parts of printed sentences. Put them in a bag and shake them up. Draw them out of the bag and construct a new piece by placing them in the new order as they emerge from the bag. Or you could try a digital Dadaist poem like this Wikipedia Dadaist poem in which I cut-and-paste at random from Wikipedia pages on Beauty, Truth and Love:-

A Dadaist Wikipedia poem

An “ideal beauty” is an entity people and landscapes considered beautiful thus associated with “being of one’s hour” localizing the processing of beauty in one brain region computer generated, mathematical average of a series of faces the opposite effect was observed when the alleged crime was swindling, perhaps because jurors perceived the defendant’s attractiveness as facilitating the crime

Some philosophers view the concept of truth as basic it is still a metaphysical faith on which our faith in science rests by adulthood we have strong implicit intuitions about “truth” that form a “folk theory” of truth as Feynman said, “… if it disagrees with experiment, it is wrong” when one says ‘it’s true that it’s raining,’ one asserts no more than ‘it’s raining’

the love of a mother differs from the love of a spouse differs from the love of food romantic attraction determines what partners mates find attractive and pursue, conserving time and energy by choosing the altruistic and the narcissistic the “feeling” of love is superficial in comparison to one’s commitment to love via a series of loving actions over time Mozi, by contrast, believed people in principle should care for all people equally

In such a serious world, the openness and joy of play, with its potential for new ways of thinking and new ways to solve problems and be creative, and especially in the trust that is created by playing games with other people, surely Surrealist games should be played by all. I hope you have an imaginative, play-filled winter holiday.

Illustration credits:

https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/surrealism/tapping-the-subconscious-automatism-and-dreams

http://gameonfamily.com/how-to-play-charades/

If, by chance, you have the desire and the opportunity to engage in creative work at the beginning of this new year then having a quiet, disciplined approach and withdrawing from the din of people and the distractions of (social) media will probably help to accomplish what you set out to do.

If, by chance, you have the desire and the opportunity to engage in creative work at the beginning of this new year then having a quiet, disciplined approach and withdrawing from the din of people and the distractions of (social) media will probably help to accomplish what you set out to do. t will supply hackneyed material such as stereotypes or over-literary characters if allowed sway during the writing process. So her ideal model of composition is one in which the unconscious and conscious take turns to be in the ascendant: the unconscious writes, then the conscious edits. “Hitch your unconscious mind to your writing arm,” she advises.

t will supply hackneyed material such as stereotypes or over-literary characters if allowed sway during the writing process. So her ideal model of composition is one in which the unconscious and conscious take turns to be in the ascendant: the unconscious writes, then the conscious edits. “Hitch your unconscious mind to your writing arm,” she advises. not try it yourself? Sit down for ten minutes and banish all logic and sense. Resolve to waste time and paper and freewrite on what your unconscious really needs and wants to be fed. Also, attempting such a nonsensical task might push that meddlesome intellect out of the way for a while.

not try it yourself? Sit down for ten minutes and banish all logic and sense. Resolve to waste time and paper and freewrite on what your unconscious really needs and wants to be fed. Also, attempting such a nonsensical task might push that meddlesome intellect out of the way for a while.