Breton’s Nadja and my novel-in-waiting

My novel Swimming with Tigers is based on a real historical person connected to surrealism in the 1920s known as Nadja.

In this post I want to share with you how I used a combination of research and freewriting to transform this shadowy figure from history into the character of Suzanne in my novel.

I hope that along the way you’ll become as fascinated as I am with her and also get some insight into how freewriting can be directly used as a novel-writing tool.

Breton’s Nadja

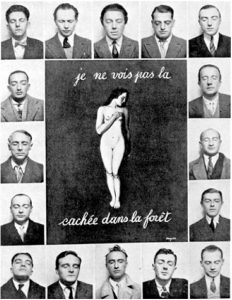

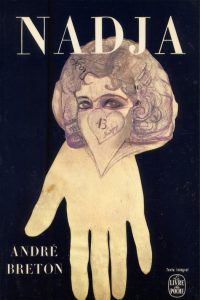

In 1926, the leader of the surrealist movement André Breton met a woman who called herself Nadja on the streets of Paris and was immediately smitten with her as a person and with her entirely original way of living and seeing things. It formed the blueprint of the  surrealist principles of chance, altered consciousness and the strangeness of ordinary things. Breton wrote a book entitled Nadja about his encounter with this elusive and unstable, visionary woman in 1928.

surrealist principles of chance, altered consciousness and the strangeness of ordinary things. Breton wrote a book entitled Nadja about his encounter with this elusive and unstable, visionary woman in 1928.

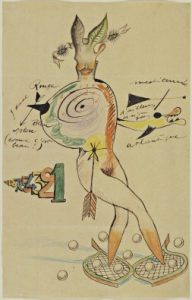

Breton’s portrait gives tantalising glimpses of her originality and frailty; she is a free spirit but cripplingly shy and insecure, with terribly low self-esteem. Nadja is a fascinating document but is, in the end, about Breton himself, and Nadja exists primarily as his creation, although some of her drawings and sayings are reproduced in the book.

By the end of his account, she is in a mental institution and Breton decides not to visit her, giving his disenchantment with psychiatry as an excuse. Instead he abandons her to her fate.

For many years there were no photographs of her except the one in Breton’s book, where her eyes are repeated in a truly disconcerting multiple arrangement. There was even some doubt about her ever having existed at all. She was believed to have died in hospital, in 1941.

Could I Put Nadja in a Novel?

Looking around for an idea for a novel, I wondered if I could tell Nadja’s story, drawing on Breton’s account, but using my own imagination. I wanted to give her centre stage this time. What a gift to a novelist! I spent quite some time searching and expecting that such a thing had already been done, but I seem to be the first to attempt to bring Nadja to life in a new novel.

Then, when I read in the introduction to the Penguin edition of Nadja that there were rumours that she didn’t die in 1941, but was living in France and working as a typist in the 1970s, my novel started to really come to life. I wanted to create a new myth to rival Breton’s, in which she did not die incarcerated but lived on, free and independent.

How I Did It

Using Breton’s book as a starting point, I re-named Nadja Suzanne and allowed myself plenty of time to conjure her up as a physical presence and to bring out all of the associations her story had accumulated. Freewriting was perfect for this and allowed me to range widely and accept unintended elements into my creation.

Here is an extract from some freewriting I did on Suzanne:-

The bird girl, the butterfly girl, the hurt girl, the disowned. The gothic ghost, the fey child, the polluted whore, the cast-off mistress, the naive poet, the schizophrenic.

The skipping girl, the coquette, the cat-like, the acrid. The heroine, the First Cause, the one carrying it all and yet not able to steer it, or say anything to it. The traumatised one, the delicate-featured.

The resurrected, the alive-all-along, the re-found. Laughing and dancing, shouting in the corridor, blazing life then grey isolation.

The thin soles, the red coat, the bare legs, the messy make-up. The one who is starved or who starves herself. Until she is fed, and befriended. Saved.

The one with magic eyes, with mirrors, with windows. The one with wings in the mind.

Gradually, my fictional Suzanne began to feel more real to me than the historical Nadja.

Writing Scenes

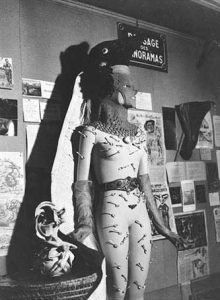

Next I wrote some scenes in which Suzanne makes a friend who saves her from despair. I named this friend Penelope and mixed in details from the lives, works and appearances of several women surrealists such as Leonora Carrington, Eileen Agar, Lee Miller and Meret Oppenheim in order to create her.

Here is part of an early scene when Penelope first meets Suzanne. By this time I knew exactly how Suzanne would appear to a stranger:-

‘Mademoiselle.’ The waiter placed a glass of red wine in front of Penelope, giving her an ingratiating smile. She watched him take the other glass from his tray and put it down at Suzanne’s place without a word.

‘He doesn’t seem to like you,’ Penelope murmured, once the waiter was out of earshot.

‘He thinks I don’t belong here,’ said Suzanne, getting out another cigarette.

Penelope looked at Suzanne dispassionately for the first time. Her clothes were cheap. The felted red coat with a dropped hem had fallen open to reveal a much-washed black crepe dress and her shoes were in ruins. Her face could do with a wash and there was a feint smell of tomcat about her, vying with a cheap, sharp perfume. Did Suzanne look like a prostitute? Was that what the waiter thought she was? What would Penelope’s mother say if she knew that her precious debutante was out in public with a woman of dubious reputation?

Suzanne was shifting awkwardly in her chair. No, she didn’t look like a prostitute, not exactly; she looked displaced.

Keeping Going

I also used freewriting to gauge and harness my personal investment in the character. Nadja said of herself (according to Breton) “I am the soul in limbo” and in the past so many gifted, creative women have remained in limbo, unknown and unacknowledged.

Much of my work as a university lecturer in literature and women’s studies has been devoted to the feminist enterprise of rescuing women writers and artists from obscurity and reassessing their place and contributions. It was this that originally drew me to Nadja.

I used freewriting throughout the composition of the novel to keep my motivation in focus and to power me through the inevitable difficulties and delays. Even now, some years later, Swimming with Tigers has yet to find the right publisher (although the manuscript was long-listed for an international prize). My commitment, however, to making the women surrealists better-known remains stronger than ever.

Who Is She?

Since I began the novel, more has emerged about Nadja including her real name which was Léona Delcourt. There is now a photograph to look at and a biography (in French). But no amount of hard fact will ever entirely banish the deeply mysterious aura around this strange and compelling woman.

In my own novel, a parallel story sets up the possibility that another character is about to meet the actual, historical, Nadja. But the Nadja of my novel is already fictionalised as Suzanne and remains, like a true surrealist ghost, both real and imaginary at the same time…

If you would like to read more on Nadja, here are some articles available on the web:-

“Something Wrong” Women Who Crash

Nadja: Surrealism’s Absent Heart

[Some of this material appeared in an earlier post.]

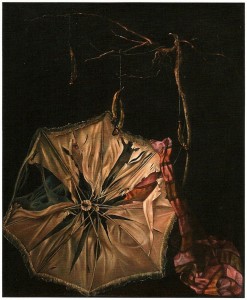

and sexy girl wannabe is repeated again and again in the lives of the surrealist women. Tanning might well have needed the “in” to the surrealist group but her talent was already formed as is clear from this astonishing picture.

and sexy girl wannabe is repeated again and again in the lives of the surrealist women. Tanning might well have needed the “in” to the surrealist group but her talent was already formed as is clear from this astonishing picture.

sunflower looking at itself in a mirror, with pin-sharp realism. But then in the later 1950s she moved into a new style of abstract but recognisable “smoky” pictures in which figures and space merge into each other. These pictures were not my favourites, but some were just as disturbing and involving as the starker and more figurative works. For instance Insomnias from 1957 gives a nightmare version of mental unease.

sunflower looking at itself in a mirror, with pin-sharp realism. But then in the later 1950s she moved into a new style of abstract but recognisable “smoky” pictures in which figures and space merge into each other. These pictures were not my favourites, but some were just as disturbing and involving as the starker and more figurative works. For instance Insomnias from 1957 gives a nightmare version of mental unease.

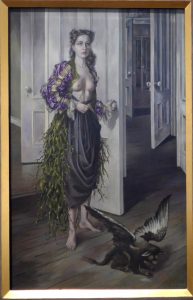

mma, too (1970). Named after Emma Bovary in Flaubert’s novel the soft sculpture of a belly was placed next to a series of watercolours of mothers and babies from the 1960s along with the well-known picture from 1946-7 called Maternity. In this painting are doors again, preventing or trapping women or perhaps holding out the possibility of escape. The simultaneously scary and amusing element in this picture is the dog with a child’s face (there were Tibetan dogs all over the place in the exhibition: she owned them and included them obsessively in her work in different guises, sometimes scaled up to human size).

mma, too (1970). Named after Emma Bovary in Flaubert’s novel the soft sculpture of a belly was placed next to a series of watercolours of mothers and babies from the 1960s along with the well-known picture from 1946-7 called Maternity. In this painting are doors again, preventing or trapping women or perhaps holding out the possibility of escape. The simultaneously scary and amusing element in this picture is the dog with a child’s face (there were Tibetan dogs all over the place in the exhibition: she owned them and included them obsessively in her work in different guises, sometimes scaled up to human size).

vulnerability of women is somewhere in the background. In Tweedy, however, we had just the joke: a fantasy tweed-covered animal with a little matching turd.

vulnerability of women is somewhere in the background. In Tweedy, however, we had just the joke: a fantasy tweed-covered animal with a little matching turd.