The Art of Making People: characters in historical fiction

If a historical novel is defined as one in which events from history are presented as they actually happened, then my unpublished novel Swimming with Tigers doesn’t qualify as one. The alterations I have made to the facts about the artists who took part in the Surrealist movement would make a historian weep!

Sometimes I’m afraid I’ll forget what I have invented, and what is based on fact. For instance, I am 99% sure I invented the Surrealist object of a bathing cap covered with snail shells but I suppose it’s always possible that I read about it. This is where research notes are crucial so that, if necessary, I can trace back the process of writing. Luckily I am an obsessive note-taker and writer of journals.

All historical fiction is a mixture of the true and the invented. Some novels take important or well-known historical figures and give us their imagined interior life (for example Joyce Carol Oates’ novel about Marilyn Monroe, Blonde or Michael Cunningham’s wonderful impersonation of Virginia Woolf in The Hours). Some authors, on the other hand, opt for the creation of characters with no specific model but who could have been close enough to observe a major historical figure and they make these ‘witness’ figures the main focus of the story (as did Jeanette Winterson with Napoleon’s cook in The Passion).

In Swimming with Tigers I have used the perhaps less common method of mixing several historical people together to create a single fictional character. My novel could also be called alternate history (such as Robert Harris’s Fatherland in which Germany won the Second World War) because one of my characters is based on a woman who died in the 1940s but I explore the possibility of her living on into the 1970s.

There are plenty of lively debates about the rights and wrongs of using ‘real’ people in works of fiction and of course there are laws against defamation. Fortunately, it’s impossible to defame the dead, and I must confess I was secretly relieved when Leonora Carrington finally passed away at the age of 94 because I had based my main character Penelope on her and, while I hadn’t portrayed Penelope doing anything illegal or bad, I knew that Leonora Carrington was a very fierce woman!

At first I was uncomfortable, as an academic, to be playing fast and loose with the truth but I drew inspiration from one of my favourite writers: Angela Carter. In her last novel, Wise Children, Carter brilliantly references a huge number of real people from Lewis Carroll to Harry Enfield, often without naming them. You could (if you really wanted to) write a companion book detailing all the writers, actors, directors, TV personalities and so  on that have been borrowed, combined and re-fashioned in Wise Children (as indeed you could for the artists and writers in Swimming with Tigers).

on that have been borrowed, combined and re-fashioned in Wise Children (as indeed you could for the artists and writers in Swimming with Tigers).

The Hollywood scenes in Wise Children are where some of the best fun is to be had. For instance Carter combines Lana Turner and Jean Harlow in her creation of Daisy Duck, and then has her follow the same TV career as Joan Crawford. The more you know of the originals, the better the entertainment but (and I noted this carefully) the success of Carter’s novel doesn’t depend on the reader knowing who the original models are, and the joke that Gorgeous George tells at the end of the pier is just as funny whether or not you know it’s based on Larry Grayson (along with a dash of Max Miller and Frankie Howerd, according to Kate Webb). With this in mind I made sure that my novel could be enjoyed by someone without any knowledge of the Surrealists.

Rather like Angela Carter’s Daisy Duck who is a mixture of different actresses, my main character Penelope is composed of several real women in the Surrealist group and she creates art-works by all of them. Penelope escapes from her wealthy background and factory-owning father in England exactly as Leonora Carrington did (although I have re-located her home from Lancashire to Oxfordshire). As did Carrington, Penelope endures the humiliation and boredom of being a debutante and runs off to Paris to join the Surrealists and has a passionate affair with one of the artists of the Surrealist group. Max Ernst was Carrington’s lover in real life, and Penelope elopes with a character called Rolf who ‘is’ Ernst but Rolf also makes Man Ray’s photographs. You see how complicated this is?

Penelope paints Leonora Carrington’s wonderful painting Inn of the Dawn Horse (I discuss this painting here) but she also makes Eileen Agar’s sculpture Angel of Anarchy (which was made in 1940, not 1938, as in my novel). Best of all, she creates one of the iconic objects of Surrealism: Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined teacup and saucer (read more here). I actually dramatise the making of this object, down to the glue being smeared onto the gazelle fur which is then pressed onto the china cup, and I can only hope that the reader will get the same thrill from reading the scene as I did from writing it.

From Meret Oppenheim I also took Penelope’s habit of balancing on high ledges of buildings and I have a scene in which she scares the others at a Surrealist party by climbing outside onto a window ledge. The party, by the way, is a costume party, of which the Surrealists were naturally very fond, but instead of the real dress code which was to be naked from chest to knee, I changed it to naked from the waist up. I did this to dramatise the sexual inequality in the Surrealist group as, for obvious reasons, going topless has a different connotation for women compared to men.

As well as making art which was actually created by Leonora Carrington, Meret Oppenheim and Eileen Agar, Penelope discovers the photographic technique of solarisation in the way that Lee Miller did (by accidentally turning on the light in a dark room when negatives were developing). It is generally Man Ray who is given credit for this innovation while Lee Miller is predominantly known (or has been, until recently) as the model in his solarised portraits. To have Penelope state that she deserves acknowledgement as the creator of the technique is my way of setting the record straight but doing it, ironically, by making things up!

To counter-balance this pick-and-mix approach to history, my presentation of place in Swimming with Tigers is absolutely accurate. This strategy follows some advice Louise Doughty gave in A Novel in a Year to someone who was writing a novel about dragons. Doughty suggested he should go and find an actual tree that his dragon might like to sit on: ‘even if you’re writing fantasy it still has to be real’ she says. So while I imagined what it was like to play Surrealist games with André Breton, I made sure that Penelope went to the café where he held court along the right street in Paris, and in the right direction.

This meant that researching the novel provided the perfect excuse for several wonderful holidays to Lisbon, Amsterdam, Cadaqués, Lille and Paris, all of which are settings for the story and I also spent some time pacing out the distances in Kingston-on-Thames where the modern, parallel, narrative is set. I felt it was important to go to every location, taking photographs and writing notes as I went. In the novel, as it was when I visited, the floor in the Café de Flore has brown and white tiles in the shape of fans, and the upper floor is reached via a spiral staircase. I don’t know for sure that the floor tiles or the black iron staircase were there in Café de Flore in 1938 but it’s possible that they were. Concrete details give the story a firm foundation for building characters on, such as Penelope who embodies the many brave, creative, spirited women of Surrealism while at the same time, I hope, standing as a believable figure in her own right.

Here are some ‘real’ history books if you would like to find out more about the Surrealists:

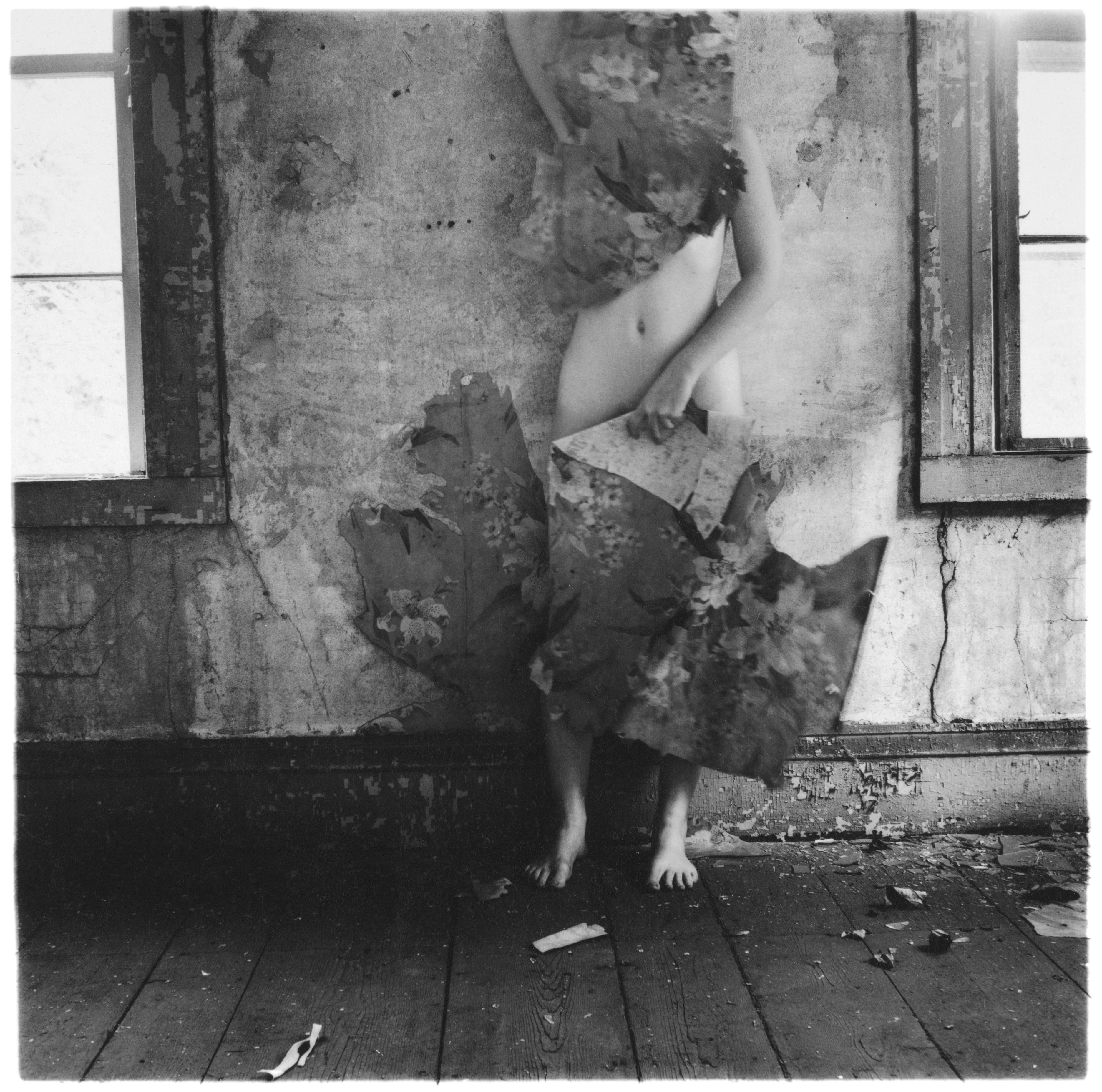

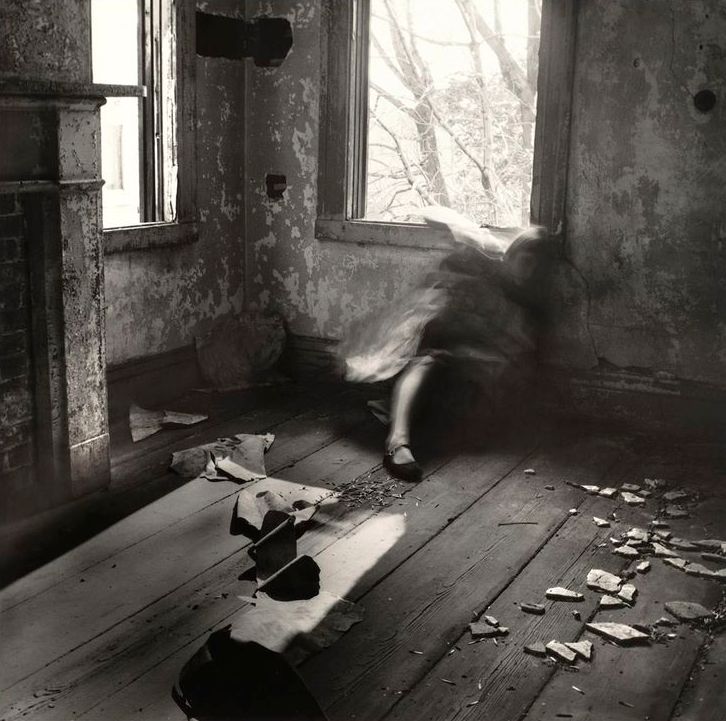

way it’s been set up and furnished, and the use of streaming natural light and blurring.

way it’s been set up and furnished, and the use of streaming natural light and blurring.

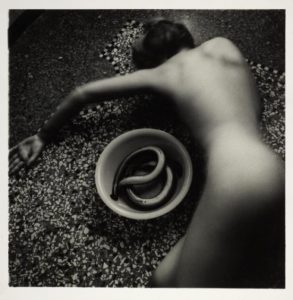

e eel representative of some phallic threat or promise next to her soft and undefended body? When I saw the picture in the exhibition it suggested to me the prospect of pregnancy: an uncanny portrayal of something curled up outside the body that might equally be furled inside. The beauty of the shapes and the textures, the lit edges of the uncanny fish and the homely bowl all contribute to make it a truly compelling image.

e eel representative of some phallic threat or promise next to her soft and undefended body? When I saw the picture in the exhibition it suggested to me the prospect of pregnancy: an uncanny portrayal of something curled up outside the body that might equally be furled inside. The beauty of the shapes and the textures, the lit edges of the uncanny fish and the homely bowl all contribute to make it a truly compelling image.