Writing for the Drawer: is private writing a waste of time?

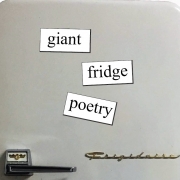

/0 Comments/in freewriting, writing inspiration/by Kathy HopewellGiant Fridge Poetry at the Metamorffosis Festival

/0 Comments/in freewriting, original writing, writing exercises, writing inspiration/by Kathy HopewellThe Blog: a guided tour

/2 Comments/in freewriting, Surrealism, writing inspiration/by Kathy HopewellIt was January 2015 when, inspired by a weekend of baking bread with Mick Hartley The Partisan Baker, I composed my first post for The Freewriter’s Companion.

I had two aims.

One was to popularize freewriting, a liberating and fertile method of smashing writing blocks and of generating material that can form the basis of stories, poems or novels.

The second aim was to promote Surrealist women artists and writers from the past such as Dorothea Tanning, Meret Oppenheim and Leonora Carrington who have been overshadowed by their male counterparts (Salvador Dali, Rene Magritte, Andre Breton, and so on).

The combination of freewriting and Surrealism was important to me for other reasons too. I had been researching a novel about Surrealism and at the same time experimenting with Natalie Goldberg’s methods of writing practice. It occurred to me that this approach to creative writing was really a Surrealist one and resembled the automatic writing that all the Surrealists practised in the 20s and 30s. I wondered why no one (apart from literary critics such as Kevin Brophy and a few others) had brought these two things together.

So I did.

I taught freewriting courses at Bangor University’s Lifelong Learning department until its tragic closure in 2017 and then launched some very successful independent courses of my own in a local cafe. Students found freewriting hugely useful, easy and rewarding and produced excellent, original work from it, often accessing their own “voice” for the first time.

I started sending out free weekly prompts via email in January 2019 and at the time of writing I have well over 300 subscribers. Along the way, some of my blog posts were particularly successful such as the directly useful Become a Writer in 10 Minutes and Six Uses for Freewriting.

People were kind enough to respond to my posts and to share in my admiration and love for a family member we lost in 2017 who turned out to have been a writer of no mean achievement.

In other posts I was able to acknowledge my gratitude to wonderful writing “gurus” such as Natalie Goldberg and Anne Lamott. In a slightly more playful mood I characterised Goldberg and other advocates of freewriting as great performers such as Bowie and Jimi Hendix.

I enjoyed the chance to explore the feminist aspects of the critical neglect of women Surrealists in a post about the Surrealist muse and was gratified that people were keen to read about the way I fictionalised the 1938 International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris in my own novel.

Also, people across the world seemed to enjoy the Surrealist Christmas games I described and my post even got a mention in The Guardian.

My blog has also been the go-to place for news and backstory on the spoken word band that my partner David and I formed in 2011 called Hopewell Ink. You can read an interview with David here, conducted by me, in which I try to persuade him to describe what Hopewell Ink is all about.

2021 sees a new departure for The Freewriter’s Companion as I launch two online courses in freewriting and I hope that my five-year blog archive will serve as a resource for people curious about freewriting, surrealism and everything inbetween.

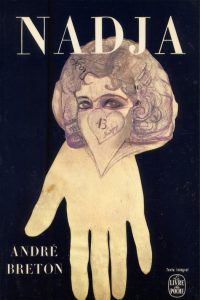

Breton’s Nadja and my novel-in-waiting

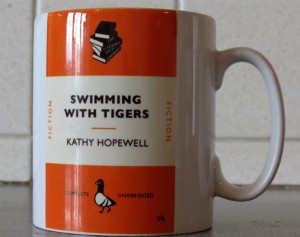

/4 Comments/in Articles about Surrealism/by Kathy HopewellMy novel Swimming with Tigers is based on a real historical person connected to surrealism in the 1920s known as Nadja.

In this post I want to share with you how I used a combination of research and freewriting to transform this shadowy figure from history into the character of Suzanne in my novel.

I hope that along the way you’ll become as fascinated as I am with her and also get some insight into how freewriting can be directly used as a novel-writing tool.

Breton’s Nadja

In 1926, the leader of the surrealist movement André Breton met a woman who called herself Nadja on the streets of Paris and was immediately smitten with her as a person and with her entirely original way of living and seeing things. It formed the blueprint of the  surrealist principles of chance, altered consciousness and the strangeness of ordinary things. Breton wrote a book entitled Nadja about his encounter with this elusive and unstable, visionary woman in 1928.

surrealist principles of chance, altered consciousness and the strangeness of ordinary things. Breton wrote a book entitled Nadja about his encounter with this elusive and unstable, visionary woman in 1928.

Breton’s portrait gives tantalising glimpses of her originality and frailty; she is a free spirit but cripplingly shy and insecure, with terribly low self-esteem. Nadja is a fascinating document but is, in the end, about Breton himself, and Nadja exists primarily as his creation, although some of her drawings and sayings are reproduced in the book.

By the end of his account, she is in a mental institution and Breton decides not to visit her, giving his disenchantment with psychiatry as an excuse. Instead he abandons her to her fate.

For many years there were no photographs of her except the one in Breton’s book, where her eyes are repeated in a truly disconcerting multiple arrangement. There was even some doubt about her ever having existed at all. She was believed to have died in hospital, in 1941.

Could I Put Nadja in a Novel?

Looking around for an idea for a novel, I wondered if I could tell Nadja’s story, drawing on Breton’s account, but using my own imagination. I wanted to give her centre stage this time. What a gift to a novelist! I spent quite some time searching and expecting that such a thing had already been done, but I seem to be the first to attempt to bring Nadja to life in a new novel.

Then, when I read in the introduction to the Penguin edition of Nadja that there were rumours that she didn’t die in 1941, but was living in France and working as a typist in the 1970s, my novel started to really come to life. I wanted to create a new myth to rival Breton’s, in which she did not die incarcerated but lived on, free and independent.

How I Did It

Using Breton’s book as a starting point, I re-named Nadja Suzanne and allowed myself plenty of time to conjure her up as a physical presence and to bring out all of the associations her story had accumulated. Freewriting was perfect for this and allowed me to range widely and accept unintended elements into my creation.

Here is an extract from some freewriting I did on Suzanne:-

The bird girl, the butterfly girl, the hurt girl, the disowned. The gothic ghost, the fey child, the polluted whore, the cast-off mistress, the naive poet, the schizophrenic.

The skipping girl, the coquette, the cat-like, the acrid. The heroine, the First Cause, the one carrying it all and yet not able to steer it, or say anything to it. The traumatised one, the delicate-featured.

The resurrected, the alive-all-along, the re-found. Laughing and dancing, shouting in the corridor, blazing life then grey isolation.

The thin soles, the red coat, the bare legs, the messy make-up. The one who is starved or who starves herself. Until she is fed, and befriended. Saved.

The one with magic eyes, with mirrors, with windows. The one with wings in the mind.

Gradually, my fictional Suzanne began to feel more real to me than the historical Nadja.

Writing Scenes

Next I wrote some scenes in which Suzanne makes a friend who saves her from despair. I named this friend Penelope and mixed in details from the lives, works and appearances of several women surrealists such as Leonora Carrington, Eileen Agar, Lee Miller and Meret Oppenheim in order to create her.

Here is part of an early scene when Penelope first meets Suzanne. By this time I knew exactly how Suzanne would appear to a stranger:-

‘Mademoiselle.’ The waiter placed a glass of red wine in front of Penelope, giving her an ingratiating smile. She watched him take the other glass from his tray and put it down at Suzanne’s place without a word.

‘He doesn’t seem to like you,’ Penelope murmured, once the waiter was out of earshot.

‘He thinks I don’t belong here,’ said Suzanne, getting out another cigarette.

Penelope looked at Suzanne dispassionately for the first time. Her clothes were cheap. The felted red coat with a dropped hem had fallen open to reveal a much-washed black crepe dress and her shoes were in ruins. Her face could do with a wash and there was a feint smell of tomcat about her, vying with a cheap, sharp perfume. Did Suzanne look like a prostitute? Was that what the waiter thought she was? What would Penelope’s mother say if she knew that her precious debutante was out in public with a woman of dubious reputation?

Suzanne was shifting awkwardly in her chair. No, she didn’t look like a prostitute, not exactly; she looked displaced.

Keeping Going

I also used freewriting to gauge and harness my personal investment in the character. Nadja said of herself (according to Breton) “I am the soul in limbo” and in the past so many gifted, creative women have remained in limbo, unknown and unacknowledged.

Much of my work as a university lecturer in literature and women’s studies has been devoted to the feminist enterprise of rescuing women writers and artists from obscurity and reassessing their place and contributions. It was this that originally drew me to Nadja.

I used freewriting throughout the composition of the novel to keep my motivation in focus and to power me through the inevitable difficulties and delays. Even now, some years later, Swimming with Tigers has yet to find the right publisher (although the manuscript was long-listed for an international prize). My commitment, however, to making the women surrealists better-known remains stronger than ever.

Who Is She?

Since I began the novel, more has emerged about Nadja including her real name which was Léona Delcourt. There is now a photograph to look at and a biography (in French). But no amount of hard fact will ever entirely banish the deeply mysterious aura around this strange and compelling woman.

In my own novel, a parallel story sets up the possibility that another character is about to meet the actual, historical, Nadja. But the Nadja of my novel is already fictionalised as Suzanne and remains, like a true surrealist ghost, both real and imaginary at the same time…

If you would like to read more on Nadja, here are some articles available on the web:-

“Something Wrong” Women Who Crash

Nadja: Surrealism’s Absent Heart

[Some of this material appeared in an earlier post.]

Freewriting in Peformance

/0 Comments/in freewriting, original writing, writing inspiration/by Kathy HopewellThis month I have four short videos of writers reading their own work for you to enjoy.

All were filmed at a free poetry and music festival in Bangor, North Wales, earlier this year. This annual festival is called “Curiad Bangor” or, in English, “Bangor Pulse” which is a great, inclusive, name covering anything with a beat, whether in words or music.

As part of this year’s festival, I organised a night of poetry and prose performances and it happened to feature some writers who had subscribed to the weekly freewriting prompts I used to send out.

Three of the performers read work that had been sparked originally by one of my freewriting prompts and although of course the work is theirs and theirs alone, it was such an honour to be credited with inspiring them to write it.

I hope their pieces will show how freewriting from a prompt can form the basis of finished work, after judicious editing.

First up is a lovely, sinuous piece of writing about jazz by Nigel Stone.

In classes on the short story or novel, an old standby of mine is to invite students to write about the strangest person they’ve ever met. Elaine Hughes produced this absolutely hilarious and yet very affectionate piece about a real eccentric with the title “The most peculiar person I ever met”. It brought the house down!

Last but not least, here’s Anna Powell. She reads two poems. I’m not sure which prompt formed the start of the first poem (“Spiders”) but the second poem, about her hearing problems, was from a prompt that she had to adapt to her own use and I like to think that it was the practice of freewriting that gave her the freedom and courage to do it. Not only has this produced an excellent poem, it also gives us much more of Anna herself and I felt priviledged to be invited into her inner world.

To round off the show, here is myself and partner David performing a Hopewell Ink piece. So far, all of Hopewell Ink’s words have arrived in a freewrite of mine. It often takes a while for the finished version to emerge but I hope that the freshness of freewriting (those “first thoughts”) remains. This is a seasonal piece that celebrates autumn but in a less-than-conventional way.

Where Does Freewriting Come From?

/0 Comments/in freewriting, Surrealism/by Kathy HopewellI began this website because, as a lecturer on Surrealism and a private addict of freewriting, I was amazed that no one seemed to connect the two.

Surrealism comes from Freud, via Breton

The Surrealist movement was kicked off by the practice of automatic writing (art came later).

Surrealist automatic writing uses essentially the same method as modern-day freewriting in which you write continuously, allowing random processes to take over and suspending all critical judgment until the end of the exercise. [If you’d like more detailed instructions, please go to How to Freewrite].

André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement, used automatic writing as the basis to develop a whole philosophy of creativity which led to an entirely new approach to the practice of poetry, art and sculpture.

Breton himself had not come up with the idea of recording an unedited stream of consciousness. This, of course, was Sigmund Freud. Breton had used Freud’s method of free association when he was a medical orderly during the First World War and began to wonder if the unconscious could be harnessed in a similar was for the making of art.

Breton was enchanted with Freud’s ideas during the war when all things German were anathema. America, however, had adopted Freud early.

The Clark Lectures by Freud

In 1909, Freud gave a series of public lectures at Clark University in Massachusetts which were designed to reach a wide audience beyond professional, specialised psychiatric practitioners.

The Clark lectures are a good, basic introduction to Freud’s ideas about the unconscious, repression and the therapeutic work of psychoanalysis.

In the second of the lectures at Clark University, Freud likens a troubled patient to a lecture hall in which there is an audience member who is making a noise and interrupting the lecture. To regain calm and order, the troublemaker would have to be thrown out and guards would have to be placed on the doors to make sure he didn’t get back in.

In Freud’s analogy, the inside of the lecture hall is the conscious mind while outside the hall is the unconscious. And the man in the audience that is interrupting the lecture stands for an unacceptable thought that has to be ejected.

This is an illustration of repression: the trouble-maker who is ejected and prevented from getting back in represents an unacceptable thought repressed from the conscious mind. These unacceptable thoughts are, like the troublemaker in the lecture hall, disrupting civilised, social life, and must be thrust violently away, out of sight.

But Freud’s most important point was that the repression will continue to cause disruption.

In Freud’s illustration, the ejected man bangs on the door and generally continues to make his presence felt. In the same way, repressed thoughts, desires and emotions, continue to make the civilised, orderly lecture hall of the conscious mind a place of strife and discomfort. The problem of repression has not been solved.

The solution is to find someone who, like the psychoanalyst, can calm the trouble-maker enough so that he can be readmitted without causing any more disruption to the lecture. Hence the therapeutic work, involving dreams, free association and so forth will identify, and readmit the repression so that it can be put under the control of the conscious mind and tranquil, normal, life can resume.

Once the trouble-maker agrees to behave properly he can be re-admitted to the lecture hall. Civilised life goes on.

Surrealism is not therapeutic

You might assume that the Surrealists adopted automatic writing as an equivalent, therapeutic activity to Freud’s free association method, but you would be wrong!

The Surrealists wanted to unleash the revolutionary power of the unconscious and change society.

Breton and his group wanted to dismantle the institutions of public life such as the church and the government in order to claim the freedom of the individual.

You couldn’t get further away from Freud’s aims of re-integrating troubled individuals into civilised society!

Freud wants order; the surrealists want mayhem!

Freud’s example of the trouble-maker made ‘safe’ for the civilised lecture theatre has an equal and opposite counterpart in one of the most extreme statements Breton ever made. In the Second Surrealist Manifesto of 1929 Breton wrote:

The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.

Now, neither Breton nor any members of the Surrealist group in Paris or elsewhere were terrorists or mass murderers in real life, but this quote shows how far Surrealism is from the normalising aims of Freudian psychoanalysis.

You couldn’t get further away from Freud’s aims of re-integrating troubled individuals into civilised society.

Where Freud wanted to bring calm and individual peace of mind, the Surrealists were interested in finding extremes, nightmare and provocation.

Freewriting now

I find it fascinating that there is such a rich, hidden history to this common writing exercise which you can find recommended in almost any guide to creative writing.

Freewriting is also often recommended as a way to work on personal issues and problems and as a way to process difficult experiences. In this way, freewriting is being used as an equivalent to Freud’s free association method for therapeutic purposes and, like the treatment of Freud’s trouble-maker in the Clark lecture, the writer’s unconscious is safely corralled on the page and inner conflict defused.

But this is to completely erase the revolutionary aims of Surrealism, which is the ‘source’ of freewriting as an artistic technique.

For Breton and others of the group, the unconscious is a dark place, and artists and writers go there at their peril, even if sometimes what emerges is humour and irony. To take Surrealism to its extreme is to be profoundly at odds with every aspect of social life and inhabit a maladjusted state.

Why I Use Freewriting

My experience is that freewriting can produce work that is much stronger, stranger and more adventurous than anything I could create by slow, deliberate, rational and planned methods of writing. On a smaller scale to the Surrealism’s ambitions, freewriting has caused a revolution in my own life, causing me to literally leave the lecture halls of academia.

But at the same time, like Freud’s treatment of the noisy audience member, I find that releasing inhibitions in freewriting and then considering the results in a calm, constructive, way does seem to keep me on an even keel.

Freewriting has magical properties!

In being aware of the source of freewriting in Freud’s extraordinarily suggestive ideas or in the outrageous, liberating attitudes of the Surrealists, I believe we can find power and agency in our writing and lives through freewriting.

If you use freewriting, I’d love to know if you find that it promotes psychological well-being (a bit like DIY Freudian psychoanalysis).

I’d also love to know if you, like the Surrealists, have experienced it as a powerful and potent source of rebellion and creativity.