Writers! Resolve to be BAD in 2019!

This New Year, instead of making all the usual resolutions to eat less and exercise more, why not resolve to be bad and have fun writing instead? Writing need not be serious, and the things we do for pleasure are ones we do the most (box sets, anyone?)

There’s no need to treat writing as work or as something you have to give up fun things in order to do. Writing can be playful, easy, colourful, absorbing and amusing if you set up a space for freewriting.

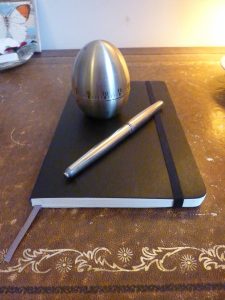

Here is mine: a battered desk at home with all my freewriting prompts and tools laid out for you to see.

In my very first post I talked about how I love the actual materials of writing and I hope by sharing my own freewriting equipment that you too will fall in love with this most enchanting and rewarding game. (I’m also hoping that, like me, you love snooping into writer’s homes, desks and notebooks.)

The Place

First of all you’ll see that my freewriting playground is full of things to awaken the senses. I can smell the dried rose petals from the garden (far right) and the recently-drunk cup of real coffee with full-fat cream. For those times when I need to mop up extraneous thought by having something to half-listen to, there are speakers to play Beethoven, Elbow or Belle and Sebastian according to mood. Finally, you can’t see this but in the tin on the left, which is where I keep all the prompts currently laid out on show, there are some gritty crystals of brown sugar left over from visits to our local cafe where (confession time!) I filch extra cubes of sugar when I go there to drink coffee and write. I’ve run out of sugar lumps at the moment, so it must be time to do a session “out” and replenish my stock (yes, I know I could buy them but that’s not the point!)

All in all, this writing station expresses the opposite of writerly privation and monastic devotion. I love Eva Deverell’s pristine white desk and perfect stationery but it just isn’t me. My desk has been through some tough handling in the past and the leather top is actually ripped open. This occurred when it was moved, wrapped inadequately in a blanket and some string, from my childhood home in Surrey. At first the damage pained me but I’ve come to love the way that this scruffy old warhorse puts me in exactly the right state of mind to make plenty of mistakes and never be precious about my writing. The lamp is also from childhood and the way in which my younger self has coloured in the design on the base with biro is also very freeing to look at! So there’s no need to spend a load of money on a perfect new writing station: old or “ruined” objects can be just as good if not better to induce a productive state of writerly mind!

Prompts

Let me explain the actual writing prompts now. These are all normally stored in the tin and drawn at random. In the centre are random phrases taken from the short story collections by Michele Roberts, Helen Simpson and Alice Munro. At 12 o’clock are my short story cards. Each set is for a story that I’m working on and they are all part of a sequence based very roughly on aspects of my own life so the cards are memories I need to write about in the fullest and free-est way possible. Next to the Reporter’s Notebook, which contains freewriting from 2005 with suggestive phrases underlined, is a set of 20 slips. On each is a specific turning point in my life and I created them according to Julia Cameron’s instructions in The Artist’s Way where she calls them “Cups” because it’s as though you have dipped a cup into the river of your life and kept a small, important moment at intervals along the way. I don’t often use these prompts but when I do I return to them with a different perspective (and different memories) each time.

The red envelope is for ideas for novels. I’m between novels at the moment and occasionally I’ll see if any of the two or three idea-seeds are beginning to sprout. I believe most of the work of creative preparation goes on below the conscious mind so I just need to do a page of freewriting now and again to make sure that the process is continuing. When the time is right, I’ll re-read these freewrites (coded “N” for easy retrieval) and decide which one to follow up.

The index cards in different colours are “germs”: ideas at a very early stage of development for Hopewell Ink (spoken word) pieces, stories and even blog posts, and I draw these at random too, using the colour-coding as a guide.

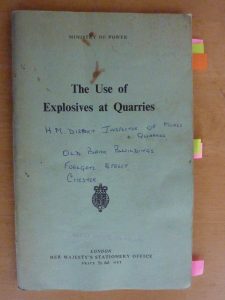

In the tin are some quotes taken from a book on quarry blasting dating from 1961 that I found at a booksale in Powis Castle this year. It was a great find!

The quote you can see is “Cartridges must be inserted into the holes carefully. Gentle pressure on the rammer may be used but on no account use violence”. Taking these quotes abstractly or tangentially I find them very suggestive emotionally and narratively and I think they might even work as sub-headings for a short story eventually. Why not try a 10-minute freewrite on that quote and see where it takes you? Or better still, find a practical manual of some kind (I have an excellent 1970s one on woodworking) and make some slips of your own to draw at random and freewrite from.

Lastly, the postcards are from Tate Liverpool or Manchester Art Gallery and the ones you can see are all of people (I have another collection of landscapes in a second paper bag underneath). These are great as prompts for in class and for my own freewriting but do need changing regularly so visits to art galleries are necessary (a great excuse, if one is needed). If you can’t get to a gallery to buy postcards, a random search on Google images might work just as well, but do beware the web: sometimes I think it’s called that because you can get caught in it and only escape hours later having done none of the things you intended. The joy of a tin of prompts is that you can exclude the rest of the world for a time: think of it as another realm or plane that you dive into, like Mary Poppins and the chalk drawings on the pavement.

Tools

The notebook you see is a gorgeous, extra-large, soft-cover, Moleskine and lying on it is my favourite fountain pen, a Cleo Skribent (this pen never leaves my desk, it is so precious). For freewriting, you can sometimes do well with scraps and bits of paper and a cracked old Bic but I love notebooks and ink pens and part of the pleasure of writing for me is to use the most luxurious I can get hold of.

The other vital bit of kit is a timer. When you are doing a timed freewrite, it’s no good at all to be continually checking the time so something like this egg timer is perfect (and nice to handle). Alternatively you could use a phone, as long as you make sure the sound and alerts are off, or an alarm clock. The other option is to just decide on a pre-set number of pages and stop when you have filled them.

Try It!

I hope I’ve inspired you to make some writing prompts of your own and set up a genuinely comfortable writing station with tools you’ll want to use. But all you really need, of course, is a flat surface, something to write on and write with, and a way of setting a limit on the time. I’ve heard that it’s possible to freewrite on a computer but don’t advise it: for me, the screen is for typing up drafts and doing the editing (then doing more editing) and for the times when I am in contact with the rest of the world.

Your freewriting station with all the toys I’ve described is where you can be free of all judgement and ambition, all measurement and stress. Just like a kid in the sandpit you can make things and knock them down again just as the fancy takes you. And every time you make a mistake you’ll learn more. The absorbed, relaxed, and joyful state of a child at play is what I seek and very often find here at my desk. I really hope you will create something similar, in your own style and for your own purposes, that gives you the same happiness and opportunity to be creative in this coming year.

If you would like to explore freewriting with me, and live in the North Wales area of the UK, please see the details about my new course “Spontaneous Creative Writing” here. I hope to develop some online courses as well later in 2019.

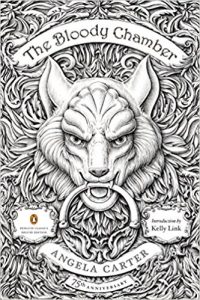

on that have been borrowed, combined and re-fashioned in Wise Children (as indeed you could for the artists and writers in Swimming with Tigers).

on that have been borrowed, combined and re-fashioned in Wise Children (as indeed you could for the artists and writers in Swimming with Tigers).